At the outset, let me explain the rationale

for writing this piece — to place in the public domain some archival

information and memories that may get lost in the mists of history. I don’t

even know whether some of the documents referred to here, and to which I had

access once upon a time, exist anymore—physically or as digitised versions.

On 22 October 1977, when Housing

Development Finance Corporation was launched by the then finance minister of

India HM Patel, at the Ball Room of Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, it was

considered a ‘revolutionary’ step in the history of Indian finance.

To understand why the concept was so

innovative, one has to understand the weltanschauung of the man who lobbied for

it unfalteringly for nearly three decades before it saw the light of the day.

One also has to understand the context of income-gearing. When jobs were so

scarce and salaries so low, how could a product based on leveraging future incomes

work?

HT Parekh articulated his concept of a

housing finance company for the first time in February 1951 when he was

employed with Harkisondass Lukhmidass, then an upcoming stockbroking firm in

Bombay. On his return from the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1936, HTP

had joined this firm on a salary of Rs150/per month, much to the chagrin of his

father, because the share market was considered a ‘sattaa bazaar’ and the term dalaal

was a pejorative. In any case, a degree in economics did not hold great

employment opportunities in India in the 1930s. At best, you could get into

poorly-paid academics or, if you were lucky and well-connected, after 1935, you

could get a job with the newly set up Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Even LSE, established by Fabian socialists

Sydney and Beatrice Webb in 1895, had a difficult time getting students as well

faculty because a degree in economics hardly led to good jobs. As AW Coats,

writing about the history of LSE, said: “The leading British economic writers

had rarely derived their inspiration or their preparatory training from

elementary economics; the number of academic economists was small;

professorships were few and poorly paid; and consequently talented men turned to

other matters, refusing to embark upon a scholarly and scientific career in

which bare subsistence is uncertain. It was, admittedly, ‘just possible to earn

enough to live with extreme economy by combining together several different

economic sources of income’…” (See: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780203978887-25/alfred-marshall-early-development-london-school-economics-unpublished-letters-bob-coats)

It was only during the directorship of Sir

William Beveridge –1919 to 1937 –that LSE was able to get distinguished faculty

members as well as students – many from developing countries. (See: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22576402-the-london-school-of-economics-and-its-problems-1919-1937). HTP was one such student from not a developing country but a then colony of

British India.

HTP was at LSE up to 1936. He had gone to

London basically to appear for the Indian Civil Service examinations but,

having failed to get selected, he completed his degree in economics at LSE. The

spirit of Fabian socialism that he imbibed during those two years was perhaps

the basis of his humanism throughout his career which was associated with

institutions of capitalism – the capital market, banking and finance.

For the current generation, who may not be

familiar with the tenets of Fabian socialism, very briefly, its advocates

believed that: 1) substantial State intervention would be necessary if ordinary

people were to prosper; and 2) the Welfare State had a collective

responsibility to its citizens for education, healthcare and nutrition, housing

and employment, along with support for care of the sick and aged.

Immediately after his return from London,

HTP taught for a few months at St Xavier’s College, Bombay. He did opt for a

career in banking like his father and elder brother, both of whom were working

with the Central Bank of India. For HTP, as he has mentioned in his

autobiographic narrative Hira ne Patro (Letters to Hira, first published in

Gujarati), AD Shroff was a role model. AD Shroff too had started working in the

share market after returning from London with a degree in economics joining the firm Batlivala & Karani (See Sucheta Dalal, AD Shroff Titan of

Finance and Free Enterprise).

So, on noticing an advertisement of Harkisondass Lukhmidass

in the Times of India for ‘educated’ youngsters to work as brokers, HTP decided

to apply. Sir Purshottamdas Thakoredas, whom HTP knew well, was an adviser to

Harkissondas; with his reference and a degree in economics from LSE, HTP got

the job. Soon, he became the ‘right-hand man’ of Harkisondass (Hakkubhai to

most people in banking and financial circles of Bombay in the 1940s and 1950s) who

used the articulation abilities of HTP to make presentations to the then

governor of RBI.

Until then, Harkisondass Lukhmidass was not

one of the firms recognised by RBI for trading in government securities. It was

at HTP’s insistence and initiative, that Hakkubhai sought a meeting with Sir

James Taylor, governor RBI in 1937 to make a presentation about their vision of

the capital market – that it is an avenue for peoples’ savings that need to be

invested in the development of the economy. ‘Presentations’ those days were all

in the nature of discussions on ‘Notes’ or ‘Working Papers’; so the domain

knowledge of the business as well as articulation skills mattered most. Harkisondass

Lukhmidass not only began to get business from RBI but also established such rapport

that Sir Taylor began to consult HTP and Harkisondass Lukhmidass on business

and economic issues. The relationship continued after Sir Taylor’s death in 1943

with CD Deshmukh who succeeded him.

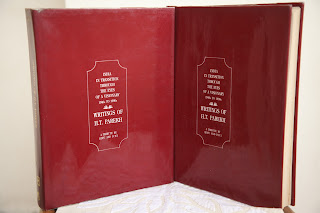

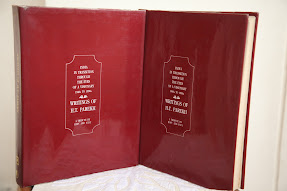

The first ‘Note’ on housing finance that

HTP wrote in 1951 was one such presentation to the Reserve Bank of India. It

was titled “A Housing Society for the Bombay State” (see India through the Eyes

of a Visionary: Writings of HT Parekh; page 467). (See:http://nitamukherjee.blogspot.com/2022/08/memories-as-archives.html)

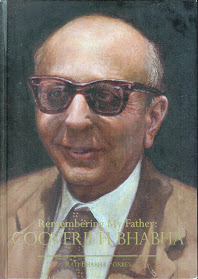

Photo: Nihar Sagar

In this Note, HTP’s emphasis was on the

financial aspects of the company – mainly on how the resources for lending

would be raised. The capital market was then in a nascent stage and, since he

was working with a broking firm, he must have observed that it would be

extremely difficult to raise money from the public. After all, if in 1955, ICICI’s

first issue of 150,000 shares had less than 2,000 applications – 1,928 to be

exact – in 1951, the situation could not have been any better. Such was the

state of the primary issues market then. (2nd Board Meeting of ICICI;

Secretary’s Board Papers; 28 February 1955).

The two tenets of Fabian philosophy, viz., a

concern for the common man and State intervention for welfare – were reflected

in this Note. The first paragraph of that Note said: “In order to assist the small

man in building residential property for himself and to assist the numerous

cooperative housing societies which have come into existence in recent years

and who require finance for housing, it would be advisable to promote an

independent housing corporation, sponsored by the government...” Further it

said: “The primary purpose shall be to advance, for residential housing of the

small man, either directly or through cooperative societies...”

Salaries in the 1950s: Interesting

Anecdotal Evidence

As mentioned earlier, HTP had joined Harkisondass

Lukhmidass in 1936 on a salary of Rs150/ per month; and although I have no

evidence for what it would have been by the 1950s, since annual increments

those days were not even in ‘three figures’, it may have been just touching

‘four figures’.

Even by the mid-1950s, ICICI – the

development bank that HTP would join in 1956 – offered salaries as low as

Rs400/- per month to the professionals it recruited. The minutes of the 1st

meeting of the board of directors of ICICI on 20 January 1955 recorded that

Percival S Beale, the then general manager, “was authorised to engage the

necessary staff of about eight to ten persons on a salary not exceeding Rs.

400/- per month.” But since Mr Beale came from the Bank of England and may not

have been too familiar with the situation on the ground, he was authorised to

do so only “in consultation with any one of the Bombay Directors of the

Company.” So, as recorded in the minutes of the board meeting, the first recruitment

advertisement of ICICI said: “We need urgently the services of one or

preferably two persons having general industrial experience, e.g., in the field

of Electricity, Chemicals, or Mechanical Engineering, who can act as the link

between our financial examination of proposals and the full technical

examination of them.” Among the engineers so recruited was Siddharth S Mehta

who came from Tata Chemicals, Mithapur after having worked in government of

India’s directorate general of trade & development (DGTD). Engineers formed

the largest percentage of initial employees of ICICI and included Suresh

Nadkarni, SS Betrabet and R Hirway.

HTP would join ICICI a year later, in March

1956, as the number 2 person in the organisation after Mr Beale. The minutes of

the 11th board meeting of ICICI on 12 March 1956 recorded, “Mr HT Parekh had

accepted the appointment as Deputy General Manager. It was resolved that Mr HT

Parekh be appointed Deputy General Manager on an inclusive salary of Rs3500/-…

from 29th March 1956.”

As a private sector institution, ICICI was

considered a good paymaster those days. So salaries in other organisations

could not have been better. In such a scenario, to develop a loan product that

would be geared on the future incomes of the borrower and from which he could

pay at least 20% each month was, indeed, ‘revolutionary’. He defined the

product as one that would offer “long-term loans for ownership housing on a

mortgage basis.... (and) enables people to own a house at the beginning of their

business career by borrowing first and repaying the debt, out of their income,

over a period of years, instead of being in a position to own one's house only

at the end of a working career, as in India.” It was even more challenging because

Indians attached a huge stigma to ‘mortgaging one’s house’ – one did that only

under dire circumstances. But what gave comfort and confidence was the fact

that the ‘small man’ in India was, by and large, regular in repayment of loans

– perhaps because moneylenders charged usurious rates and the cost delinquency

was very high – not just financially but socially as well.

HTP said at the launch of HFDC: “Better

housing and living conditions for our people is a dream I have always nursed,”

and he would lobby tirelessly to make a housing finance institution to see the

light of day. If I recollect right, it was this concern for the ‘small man’

(which, I would l always change to ‘common man’ while editing his writings), that was reflected in the fact that among the projects

that were sanctioned in the first year of HDFC’s operations was a housing loan

project for tea garden workers.